Definition, infographic, and examples that illustrate why this phrase is used ad nauseam everywhere

In Latin, quid pro quo literally means “something for something.” Quid pro quo is an arranged exchange of services or favors between two parties. It’s not formalized with a contract, and often isn’t even disclosed.

In this piece, we’re going to look at how the phrase is used in diverse matters such as law, politics, business, and more.

Jump to ↓

| Legal meaning | Quid pro quo infographic |

| History and etymology | In politics |

| At work (harassment, Title VII, etc) | In education |

| In business | In culture |

| Quid pro quo examples in a sentence | Pro bono work |

Legal meaning

According to Black’s Law Dictionary, quid pro quo is “an action or thing that is exchanged for another action or thing of more less equal value; a substitute.”

As Prof. Jed Lewinsohn noted in Yale Law Journal, “in the ordinary quid pro quo exchange, each party agrees to do their part in order to get the other party to do theirs; each conditions their own willingness to perform on the willingness of the other; and each regards the other as obligated to do their part in light of their agreement.”

That said, quid pro quo often appears in a more negative light, with implications of criminal activity in various spheres.

| Black’s Law Dictionary The most widely cited law book in the world, the new 11th edition of Black’s Law Dictionary is a must-have for legal bookshelves |

For instance, quid pro quo sexual harassment is indeed immoral and illegal since it is a form of workplace harassment under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. On its face however, a ‘quid pro quo’ itself has no moral value.

The term may reference a tacit cultural expectation. It could be a form of bartering, with both parties agreeing to terms: “I paint your fence, you mow my lawn.” Say that you help a friend move. You might expect them to buy you pizza or a drink afterward, and your friend may feel obligated to do so. (After all, a friend who doesn’t provide any “quo” could find fewer takers the next time they need a favor done.)

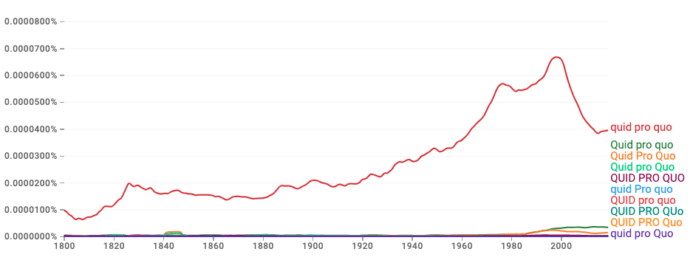

Quid pro quo has acquired negative connotations over the last few decades, ones often connected to illegal activity. The term has become more and more associated with political and business corruption, and with quid pro quo sexual harassment.

Its inescapable prevalence these days could even inspire a cynical belief: that the root of much human interaction is a selfish one, in which a person will typically expect reciprocity for doing their job as a teacher, a boss, or an elected official.

As the saying goes, “you scratch my back, I scratch yours.”

| Practical Law Practice Note An at-a-glance chart describing state and local laws that require workplace sexual harassment prevention training.View practice note with free trial |

Infographic — Quid pro quo: How it’s used virtually everywhere

What is the origin of the phrase quid pro quo?

Usage of quid pro quo began in apothecaries from the 16th century. In the middle of the last millennium, when “quid pro quo” first came into use, it had a specific connotation that hasn’t survived the years. (Ironically, the phrase doesn’t appear in any surviving Latin texts— it’s always been an English usage of Latin words.)

As per the Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest known use of “quid pro quo” comes from a translation of a treatise by Erasmus, circa 1535. This refers to a practice of apothecaries (the pharmacists of their era) in which they substituted one drug for another, or adulterated the contents of a drug for sale.

As per Erasmus, the excuse that apothecaries gave at the time was that if they didn’t swap in cheaper drugs for costlier ones, or water down their medicines with inferior ingredients, they would soon go broke.

“Quid pro quo, one thing for another,” Erasmus wrote, “they do otherwise sell this thing for that thing.”

“I find the Erasmus quote interesting in that Erasmus, like all European writers of his age, wrote in Latin. Erasmus was Dutch and would have spoken Dutch for day-to-day life but wrote in Latin, the continent-wide lingua franca,” says Tom Zielund. Tom is an Associate Architect of Information Systems for Thomson Reuters Labs with a background in Psycholinguistics.

“So, why, in translation to English (and probably not by Erasmus himself), was this particular phrasing ‘quid pro quo’ not translated with the rest of the Latin original? It suggests that the Latin phrase was already used in spoken English by that time, at least for this particular practice of apothecaries.

According to Tom, here’s how quid pro quo can be defined and broken down:

- In its most benign form, the arrangement is cooperative — you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours.

- When used in a legal context such as sexual harassment law, the arrangement is often coerced — for example the abuser withholding an earned promotion in exchange for illicit favors.

- In a political context, the arrangement is often corrupt — for example covertly bribing a politician with trips and expensive meals if they vote in a lobbyist’s favor.

The evolution of the meaning with lawyers and politics

This usage had died out by the 1800s. Long before then, however, the meaning of quid pro quo that we still use today—that of “something given in return for something else”—had become prevalent. The phrase is found in legal texts before the age of Shakespeare. As Ben Zimmer said in an NPR piece on the phrase, “lawyers love using Latin.”

Its connection with questionable political activity is also centuries old. In 1801, the Hartford Courant, then a newspaper affiliated with the Federalist Party, used “quid pro quo” to headline an article detailing how President Thomas Jefferson had rewarded a trio of Congressmen who had voted for him over Aaron Burr by giving each Congressman a new position, such as U.S. marshal.

In politics

During the 2016 presidential elections, there were allegations of Russian interference and a Trump-Russia quid pro quo. An opinion piece claimed that the Trump campaign and the Kremlin had an overarching deal to, “help beat Hilary Clinton for a new pro-Russian foreign policy.”

The concept of quid pro quo has also been central to regional political scandals. In 2018, Sheldon Silver, former speaker of the New York Assembly, was convicted on federal corruption charges. As speaker, Silver allegedly arranged to have the State Health Department award grants to Robert Taub, who ran a cancer research clinic. In exchange, Dr. Taub referred his cancer patients with legal claims to a law firm associated with Silver, who allegedly got a portion of the fees.

There was also Dean Skelos, former New York State Senate majority leader, who was convicted for allegedly pressuring business executives into giving his son Adam approximately $300,000 in bribe and extortion payments for services rendered. As per the NY state attorney, “Dean Skelos and Adam Skelos were able to secure these illegal payments through implicit and explicit representations that Dean Skelos would use his official position to benefit those who made the payments, and punish those who did not.”

In the workplace

Uninvited romance at work may lead to sexual harassment, retaliation, favoritism, and workplace violence. Quid pro quo sexual harassment is one of two types of workplace harassment claims which fall under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (the other is hostile work environment harassment). Title VII expressly protects employees from any workplace discrimination on the basis of sex.

Such quid pro quo harassment is generally defined as when a supervisor seeks sexual favors from someone under their supervision. A common example is when the supervisor asks for sexual favors in return for approving a promotion or giving the employee a raise.

| Practical Law Practice Note Workplace harassment practice note.View practice note |

There’s also “detrimental” quid pro quo harassment. Here, a supervisor will, for example, threaten to imperil the employee’s job, via giving them a poor performance review or a demotion, unless they agree to a sexual relationship.

You don’t have to be a current or former employee to claim quid pro quo harassment—prospective employees may do so too, in some cases. For example, if you applied for a job and were told by the hiring supervisor that they would recommend you in exchange for sexual favors, such harassment would fall under Title VII quid pro quo parameters and you could sue.

But an employee can’t claim quid pro quo harassment if the alleged harasser doesn’t follow through on their threat or promise (so for instance, if a supervisor gives a promotion to an employee despite the latter rejecting their overtures). Such harassment instead falls in the category of “hostile work environment” harassment.

In education

Quid pro quo harassment in education works along similar lines as quid pro quo workplace harassment. Again, this entails someone in a position of power (here, typically a teacher or professor) offering something to a student in exchange for sexual favors. The offer in this case could be a professor’s positive recommendation or a teacher giving the student a good grade in a course or on a test.

The key difference is that this type of quid pro quo harassment will fall under Title IX protection.

In business

Corporate counsels need to beware of scammers that leverage quid pro quo deception in the business world.

Insider trading

However, insider trading is a more commonly known type of financial crime related to quid pro quo exchange. A company’s employee gives non-public information about their company to someone outside the firm, who then uses that information to make a trade or investment.

To prove the tipper’s liability or violation of fiduciary duty, a court often has to determine if the two parties had entered into a quid pro quo arrangement.

- This boils down to whether the tippee’s actions financially benefited the tipper.

- Did the tippee pay the tipper for the information, provide a service to them, or cut them a share of the trading profits?

- Did the tippee’s actions materially benefit the insider’s own holdings in their company?

For example, the tipper learns of an acquirer’s potential interest in their company. They tell someone at an institutional investor, who makes a substantial stock purchase in anticipation of this news. This trading activity may be noticeable enough to raise the company’s stock price, which thus increases the value of the tipper’s stock holdings.

Other business examples

There are also more positive usages of quid pro quo in business.

An earn-out clause in a merger agreement may be considered a quid pro quo. Here the seller of a business agrees to terms with the buyer that if the sold company achieves a specified set of goals (strong earnings, higher market share, etc.), the seller will get a greater payout after a defined period. The buyer thus gets the seller’s commitment and aid to make the acquisition a stronger-performing company, while the seller gets more money for doing so.

Or take another example – incentive programs that are designed to encourage employees to achieve a set of goals. For instance, a vendor runs a contest in which the salesperson who gets the largest amount of new commissions over a given period will receive a cash prize or get an uptick in pay.

Of course, a downside to such contests is the implicit threat that the employees who underperform in this type of quid pro quo arrangement could be in danger of losing their jobs.

As Alec Baldwin memorably put it in Glengarry Glen Ross, where his character shakes up a struggling real estate sales office with a sales incentive: “first prize is a Cadillac El Dorado. Second prize is a set of steak knives. Third prize is you’re fired.”

In culture

Baldwin’s rant is one of many memorable examples of quid pro quo in American and global culture—you’ll likely come up with other examples by recalling any number of films or television shows over the past 50 years.

Take for instance the opening scene in The Godfather. An undertaker asks Don Corleone, the head of a mafia family, to avenge an insult to his daughter. Corleone agrees to do so, with the agreement that one day, he may ask the undertaker to do a service for him. As it turns out, the undertaker is summoned to arrange the funeral of the Don’s brutally murdered son.

Indeed, a good indication of villainy is when a character offers or accepts a quid pro quo—it’s a concept often associated with mob families and serial killers. “Quid pro quo. I tell you things, you tell me things,” Hannibal Lecter tells the investigator Clarice Starling in Silence of the Lambs, as his terms for cooperation in a murder investigation. Or Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train, in which a psychopath offers a quid pro quo to a stranger that he meets—each will murder someone that only the other knows, to remove any police suspicion.

In broader language with usage examples

It’s important to separate the idea of quid pro quo from similar concepts which have no negative meanings. For one thing, many people will do favors for friends or even strangers with no expectation of being rewarded. They may even be offended if you offered them a financial reward for their actions. Certainly, many people will appreciate it if someone whom they helped lends them a hand in the future.

But appreciation is different from a sense of expectation.

In the legal industry, pro bono work is a healthy alternative to the negative connotations of quid pro quo. Lawyers devote substantial time and labor to underprivileged clients and to causes that are important to them. Here there is no expectation of being rewarded financially or even reputationally.

Instead, a lawyer who provides pro bono services receives the satisfaction of knowing they’re doing good for others. It’s a good reminder to keep grounded—to do your part to ensure that everyone, regardless of their financial circumstances, deserves adequate legal representation.

Example of diverse perspectives and uses of the phrase

|

|

|

Pro bono work

Pro bono publico is another Latin phrase that is the opposite of quid pro quo and means “for the public good.”

Perhaps you’d agree it feels as if some form of reciprocity has become inextricable from politics and the workplace. It’s important to remember that this doesn’t have to be the case.

That concept, of doing a service without reward, should hold as much weight in one’s personal and professional life as does the idea of getting something in exchange for something.

| TrustLaw Through TrustLaw, the Thomson Reuters Foundation connects NGOs and social enterprises with free legal assistance.Join the mission |

Originally published by Thomson Reuters on July 20, 2023.

Chris O’Leary is a freelance writer and editor based in western Massachusetts. He is the managing editor of Thomson Reuters “The M&A Lawyer” and “Wall Street Lawyer,” and is also the author of two books on popular music.

Tom Zielund has masters degrees in cognitive psychology and computer science with emphasis on psycholinguistics. He is currently an Associate Architect of Information Systems for Thomson Reuters Labs where he helps manage the quality of data used for training models with machine learning.