Jump to ↓

| What is considered fraud, waste, and abuse? |

| How to prevent, detect, and investigate FWA |

| Choosing the right solution |

Though the pandemic is officially over, much of the fallout remains. For government agencies, one of the most challenging ongoing consequences is the prevalence of fraud, waste, and abuse (FWA) of benefits programs. The pandemic period saw a massive increase in case volumes from benefits applicants and businesses making claims for Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) funds or committing healthcare fraud with health insurance. At the same time, most agencies were unable to increase staffing and budgets to manage the added burden. As a result, despite their hard work and best efforts, they weren’t always able to verify and investigate every claim.

The situation isn’t likely to improve anytime soon. The Thomson Reuters Institute recently released the 2024 Government Fraud, Waste, and Abuse Report, which covers emerging threats and how agencies are working to address them. For the report, the Thomson Reuters Institute surveyed managers and staffers from all levels of government—federal, state, local, and municipal. The report notes that 45% of survey respondents expect FWA to increase in the near future.

Addressing and understanding fraud, waste, and abuse is crucial for any organization to maintain ethical standards and ensure efficient use of resources just like the Office of Inspector General (OIG) and the federal government aim to do. For government agencies managing benefits programs, this takes on special urgency, since making certain that people receive the benefits they often desperately need is essential to fulfilling their mission.

Though government agency leaders and staff certainly know about FWA, the challenges of battling these problems require them to be informed about current best practices involving prevention, detection, and investigation, and how technology solutions can help them in the fight.

What is considered fraud, waste, and abuse?

These are terms that to some might seem almost interchangeable. And in some cases, there may be overlapping. But in general, there are distinct problems for fraud, waste, and abuse:

Fraud

Fraud describes a dishonest and deliberate course of action that results in obtaining financial benefits to which they’re not entitled. Conflict of interest, kickbacks, potential fraud, scams, unnecessary costs, intentional deception, and misrepresentation—all signs that potential fraud is going on. And if there is financial damage, reimbursement will follow course. Fraud is a high-level risk. These examples will be all too familiar to most government employees, though there certainly are numerous other types of fraud:

- Applying for and receiving benefits or payments—such as welfare, veterans’ benefits, Social Security, Medicaid, and Medicare–to which the applicant isn’t entitled. Fraud involving the PPP program has caused great embarrassment for the government. Case in point: In February 2024, two Georgia residents were convicted of defrauding the government $11 million in illicitly obtained Covid relief funds.

- Charging for goods and services that weren’t provided. This is a particular problem, of course, when agencies are working with outside vendors.

Waste

This refers to careless spending or improper use of government money, and it can include incurring unnecessary expenses or mismanaging resources or property. These activities—or lapses of activity, if you will–don’t typically involve personal gain but usually are signs of poor management. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) identifies these three potential causes of waste:

- Mismanagement of assets. This is often caused by not keeping track of purchases. An example from the GAO: Spending money on unused or redundant software licenses because the agency wasn’t attentive to what it already had.

- Ignoring agency policies and statutes. An example of this kind of waste is when an agency executive selects vendors without following proper bidding or purchasing protocols.

- Lack of adequate oversight. Waste also can occur when an agency doesn’t establish clear guidelines or performance measurements of the programs it manages.

Abuse

This is the intentional, wrongful, or improper use or destruction of government resources or seriously improper practice. These are practices that can’t be described as fraud per se. But abuse does typically cost taxpayers money—and abuse of public resources can seriously harm the public’s perception of a government agency or even an entire administration. Examples include:

- Excessive or improper use of an employee’s or official’s position in a manner other than its rightful or legal use.

- Engaging in unnecessary or overpriced travel.

- Making purchases that are unnecessary and/or expensive.

How to prevent, detect, and investigate FWA

Despite best efforts and best intentions, federal, state, or municipal government agencies often struggle in their battle against fraud, waste, and abuse. Agency leaders and staff are undoubtedly familiar with most of the challenges. Trying different methods to improve risk management. Many involve a lack of resources, particularly because of tight budgets. Meanwhile, workloads have been increasing, and even when agencies have budgets that allow them to hire additional staff, it has been difficult to find people who are truly qualified. That can be especially true when agencies or law enforcement need to hire skilled investigators to pursue fraud, waste, and abuse cases.

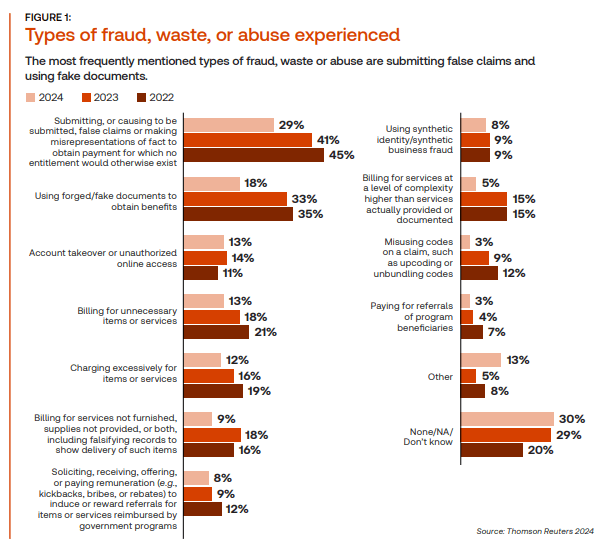

The types of fraud that agencies are battling have generally not changed a great deal. According to government employees surveyed in the Thomson Reuters Institute’s 2024 Government Fraud, Waste, and Abuse Report, false claims and forged documents remain the most common forms of fraud, waste, or abuse.

Based on previous Thomson Reuters surveys, this has been consistent from 2022 to 2024, though it may be worth noting that the percentages of respondents citing these methods has decreased, from 45% to 29% for false claims and from 35% to 18% for forged documents. Other forms of FWA identified by respondents include account takeover and using synthetic identities.

Still, the techniques that fraudsters are using have become more sophisticated. And increased workloads and outdated tech just add to the problem.

Given the current challenges that agencies are facing, it’s essential that they follow current best practices as they battle to curb fraud, waste, and abuse:

Prevention

- Front-end prevention. This type of fraud prevention involves thoroughly vetting benefits applicants and vendors at the time when they first engage with the agency for benefits, funds, or contracts.

- Identity validation. This is a crucial part of the vetting process. Agencies need to be as sure as possible that an applicant really is who he or she claims to be—and not a fraudster or identity thief seeking funds to which they’re not entitled.

- Looking into reports. When someone fills out a “Report fraud” form or calls a hotline to provide contact information or details, that can give time to agencies to prevent fraud from occurring.

Detection

- Cross-referencing databases of benefit recipients. These databases can include prison records, death records, and lists of unemployment insurance beneficiaries. To effectively detect FWA, agencies need to monitor and respond to anomalous and suspicious activity.

- Hiring additional staff devoted to FWA work. As discussed, this isn’t always an option for an agency that’s under budget restrictions. But agencies should push for it whenever necessary. In the long run, adding skilled staff can save more money than it costs.

- Using the most up-to-date technology tools. Outmoded technology can slow detection efforts by making it harder to quickly access information.

Investigation

- Deep-dive investigations. These types of fraud investigations are essential when an agency needs additional information on high-risk benefits applicants (including vendors) or an incident of potential FWA. Deep-dive investigations require additional resources, including investigators trained in more advanced techniques and tools.

- Accessing public databases. Agencies should connect with as many databases, with as wide a range as possible, so that they can determine whether a suspected instance of FWA was caused by someone locally or from someone outside the agency’s geographic domain.

- Case management technology. With staffing and resources under strain, many agencies have been incorporating digital case management solutions into their FWA investigative work—and finding that these tools are saving them time while boosting their investigations’ success rate.

Choosing the right solution

While case management technology can boost agencies’ efficiency and success rates in investigating FWA instances, based on the 2024 Government Fraud, Waste, and Abuse Report, a surprising 70% of respondents surveyed reported not having a case management solution at all. While budget or resource limits can be difficult to overcome, case management solutions can help agencies combat FWA cost-effectively, even without adding staff.

Choosing the right platform requires careful due diligence. What agencies should look for is a solution developed to address the specific needs of FWA investigators. An example of such a digital tool is Thomson Reuters Case Tracking, a case management solution used by 15% of respondents whose agency incorporates case management technology. That 15% was higher than any other case management solution currently on the market. Case Tracking manages, tracks, and investigates cases in a single, secure platform, giving investigators a complete picture of each case. The benefits this central investigative platform provides include:

- Sharing information across agency teams. Verify data and review all records in one place, which can be leveraged by different team members for easy review.

- Centralized, secure case documentation. Agency FWA teams can create notes, calls, and tasks; they also can easily add documents, images, videos, and other evidence.

- Customizable case management workflow. Case Tracking’s fully integrated system simplifies case creation and management of relevant data.

|

|

Thomson Reuters is not a consumer reporting agency and none of its services or the data contained therein constitute a ‘consumer report’ as such term is defined in the Federal Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), 15 U.S.C. sec. 1681 et seq. The data provided to you may not be used as a factor in consumer debt collection decisioning, establishing a consumer’s eligibility for credit, insurance, employment, government benefits, or housing, or for any other purpose authorized under the FCRA. By accessing one of our services, you agree not to use the service or data for any purpose authorized under the FCRA or in relation to taking an adverse action relating to a consumer application.