Risk-benefit analysis can help with decision-making. Learn best practices, frameworks, and tech solutions for risk professionals.

A business is pitching to an overseas customer promising millions of dollars in sales each year. A tech startup approaches a government agency with a digital solution that could deliver significant efficiencies in time and resources. But how can organizations like these determine whether a customer, vendor, or other potential partnership will be profitable—or perilous?

During risk analysis, risk professionals need to weigh the benefits along with the potential dangers to make the right choice on whether to proceed with the opportunity the risk may provide. We’ll explore current best practices—including technology solutions—that can help both private- and public-sector risk professionals make more confident and profitable risk decisions.

Jump to ↓

Decision-making frameworks

Risk-benefit analysis for risk and fraud professionals is a structured approach to evaluate potential risks against expected benefits to make informed decisions. It involves quantifying both the likelihood and impact of risks alongside the potential gains to determine if a particular action, strategy, or control measure is worthwhile to implement.

Most risk professionals use some form of risk-benefit analysis in their work to guide their decision-making. To optimize this methodology’s effectiveness, a key best practice is developing a rigorous decision-making framework that follows a set of methodical steps.

Establishing decision criteria

The first step is to clarify the fundamental considerations of the risk decision. Decision criteria aren’t quite the same as risk assessment calculations, which focus primarily on managing and mitigating potential negative outcomes. A risk-benefit analysis scrutinizes not only negative consequences but also potential positive ones.

One approach is to create a decision tree to evaluate both the potential costs and positive benefits of taking on a risk. This helps clarify an organization’s decision threshold—that is, a specific level of risk or benefit that can guide decision-making. Establishing decision criteria requires a realistic appraisal of the benefits of a successful outcome as well as the costs if the decision doesn’t work out.

Determining risk appetite

The organization then needs to determine how much uncertainty and potential losses are “acceptable.” Quantitative metrics include potential returns or costs and whether the organization has the size, financial stability, and resources to take on such losses or expenses, can help determine potential risk appetite for each decision.

Identifying an acceptable risk-to-reward ratio

From there, the organization begins to weigh all potential costs and rewards. In the investment world, this metric is also known as risk-adjusted return. As a rule of thumb, the acceptability of risk-to-reward ratio ranges from 1:2 to 1:3, meaning that the potential rewards would be double or triple the potential losses.

Addressing timing considerations

There are several such considerations that can affect the risk-benefit equation. For instance, an organization might have to move quickly on an onboarding decision for competitive reasons. Moving too fast, however, can leave a business or agency vulnerable to unanticipated dangers, such as the possibility of fraud.

Considerations and trade-offs

As part of the risk management framework, rigorous risk-benefit analysis can help guide risk decisions that require consideration of numerous different factors. Using risk scores may help you consider everything.

One set of factors is the influence of various stakeholders. Depending on the organization, these can include regulators, board members, customers, and (in the case of government agencies) taxpayers and administrations.

There is also the challenge of balancing seemingly competing objectives, both of which are necessary for operational stability:

- Profitability versus compliance. For example: A potentially lucrative new customer or vendor may turn out to be out of compliance with crucial regulations, which can put an organization at risk for penalties and reputational damage.

- Innovation versus security. Organizations need to balance risk-taking that can deliver new opportunities with protection from risk-induced threats (data breaches, for instance).

- Efficiency versus oversight. Properly evaluating and monitoring risk requires investments of time and resources, which some internal stakeholders might see as hindering operational nimbleness.

In some decisions, organizations must address ethical principles such as fairness and equity when determining a course of action.

There’s also the issue of short-term and long-term tradeoffs. The easiest choice is to play it safe. But avoiding risk comes with risks of its own. Taking a pass on a particular customer or vendor could result in lost opportunities for greater efficiency or profitability. A risk-benefit analysis should always weigh opportunity costs—that is, the potential benefits that might be sacrificed if it chooses a less risky option.

After following the steps of a thorough risk-benefit analysis, the organization can then decide to:

- Accept the risk as is.

- Reject the opportunity entirely.

- Accept the risk but seek ways to make the risk-reward profile more favorable. These usually involve writing protections into the transaction, contract, or other document defining the relationship between the organization and an outside party.

Implementing decisions

A thorough risk-benefit analysis also provides transparency. To use a school-math metaphor, in this methodology, risk analysts need to show their work. By clearly demonstrating that the proposed risk decision addresses every consideration, objection, and potential problem, the risk-benefit analysis is more likely to earn buy-in from internal and external stakeholders.

Once the organization decides to take on a risk, it should monitor the situation to mitigate any problems that might arise. This might entail making adjustments within a customer or vendor partnership to protect the business or agency (as much as possible) from negative outcomes.

No matter how rigorously an organization conducts its risk-benefit analysis, some decisions may not pay off. Risk professionals can incorporate what they learn from these negative outcomes into future decision-making processes, particularly regarding higher risks with the potential for greater rewards. All this means that one of the best ways to prevent adverse risk outcomes is thorough front-end due diligence of customers, vendors, and other parties offering opportunities with elements of both risk and reward.

Minimizing the risk with technology

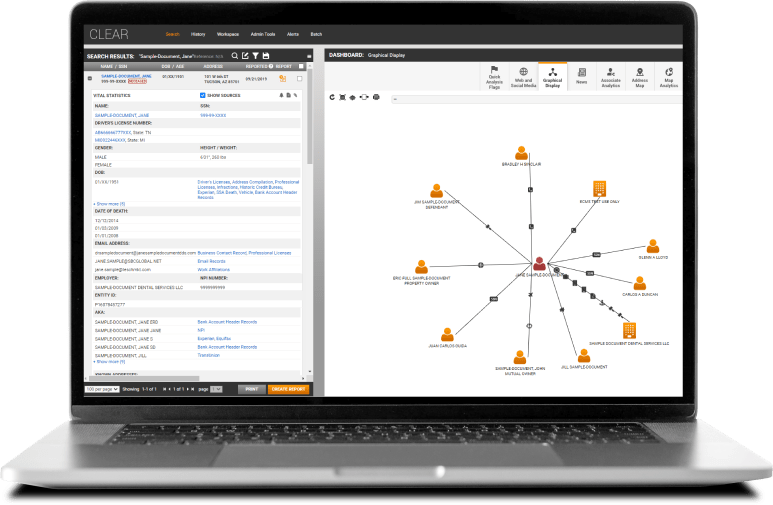

Technology can ease the burden of balancing all these considerations and drive minimal risk. Case in point: CLEAR by Thomson Reuters, a Risk & Fraud Solution, can prevent fraud, detect risk, and investigate crime with powerful online investigation software

It can help risk professionals make more informed decisions by:

- Make confident decisions with access to CLEAR’s current and trusted data

- Easily identify and analyze your subject’s connections

- Access advanced analytics powered by AI machine learning

- CLEAR powers corporate and government professionals throughout their investigation workflows

Thomson Reuters is not a consumer reporting agency and none of its services or the data contained therein constitute a ‘consumer report’ as such term is defined in the Federal Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), 15 U.S.C. sec. 1681 et seq. The data provided to you may not be used as a factor in consumer debt collection decisioning, establishing a consumer’s eligibility for credit, insurance, employment, government benefits, or housing, or for any other purpose authorized under the FCRA. By accessing one of our services, you agree not to use the service or data for any purpose authorized under the FCRA or in relation to taking an adverse action relating to a consumer application.