Actionable steps for legal teams to identify, assess, and communicate business risks

Over the past decade, the role of in-house counsel has evolved beyond providing legal advice to becoming a central player in managing company risk. Today, this evolution is not just a trend but an expectation.

This expectation is logical as the legal department is uniquely situated to connect legal compliance, strategic decision-making, and business operations. This means in-house lawyers must be able to identify and assess risk both in terms of its downside and potential rewards.

Unfortunately, most in-house lawyers still receive little formal training in how to evaluate or manage risk effectively. For the most part, dealing with risk is a self-taught skill. Assuming that this isn’t changing any time soon, the solution is twofold.

First, in-house lawyers must learn to recognize and evaluate risk in a structured way, using a framework that is aligned with business priorities.

Second, they must recognize that they cannot do it alone. Risk analysis and management are cross functional and require the legal department to develop relationships across multiple functions. Collaboration is the only way to properly review risk and to drive value creation while minimizing value destruction. Below we discuss how in-house lawyers can do both.

Jump to ↓

Step two: What you need to know

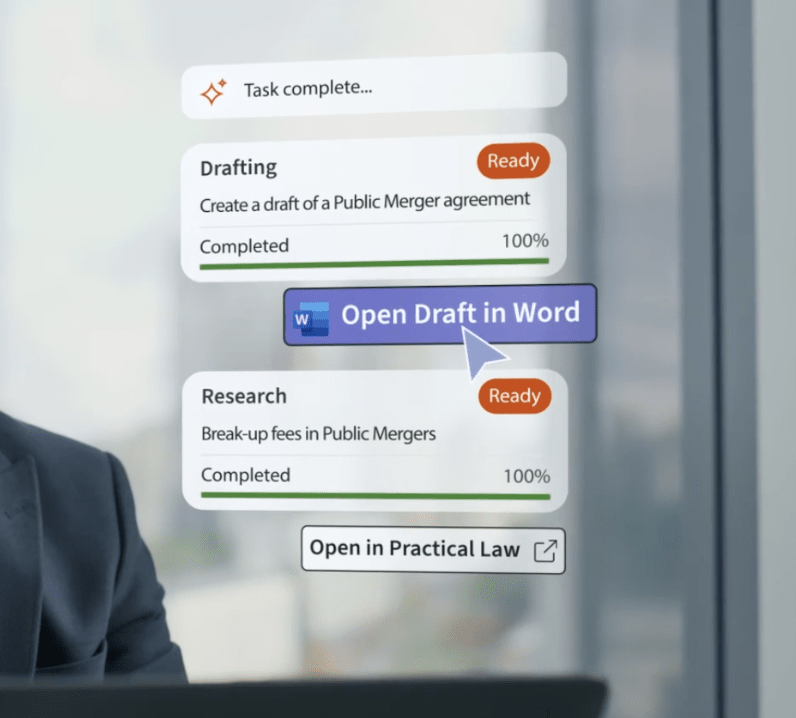

CoCounsel

Bringing together generative AI, trusted content, and expert insights

Free CoCounsel demo ↗What is risk?

When lawyers talk about risk, they often default to “worst-case” scenarios: lawsuits, fines, data breaches, investigations, and bad headlines. That is simply how they are taught to think. But this is an incomplete picture. In business, risk is not inherently negative. Companies take risks because of the upside. Without risk, there’s no innovation, no market entry, and no strategic advantage. A risk-free business is a dying business.

Risk can be both positive and negative, which makes things complicated. There are downsides and upsides with legal issues, digital transformation, ESG demands, geopolitical instability, AI, and a constantly shifting regulatory environment

The key for in-house counsel is to shift from a “no-risk” mindset to a “smart-risk” mindset — evaluating potential action or in-action based on overall business impact and probability of occurrence, not just legal exposure. Think of risk as a continuum: on one end lies “value destruction,” such as regulatory penalties or reputational damage.

On the other end is “value creation,” such as entering a new market or launching a disruptive product. Your job is to understand where a decision falls on the continuum and advise on how to maximize benefits while minimizing downside.

Types of risk

To help structure risk analysis, it is useful to divide risk into three categories:

- Legal risk: This includes areas lawyers navigate regularly, such as regulatory non-compliance, litigation, data privacy breaches, contract disputes, intellectual property claims, and employment law violations.

- Strategic risk: This includes areas of concern for business professionals, such as market shifts, financial issues, competitor activity, M&A decisions, and pricing or product strategies.

- Mixed risk: This is the middle zone where legal and business concerns overlap. Examples include ESG disclosures, use of AI, supply chain instability, or changes in data protection laws like the EU’s AI Act or US state privacy statutes. There are legal and business issues apparent in all of these. Mixed risks are becoming the norm, and this is where the in-house legal team can add the most value to the company.

Recognizing the category of a risk is crucial in defining your role — whether as a subject-matter expert, strategic advisor, or both. Below are five steps to enhance your approach to risk management.

Step one: Get looped in

Align yourself with your company’s Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) function if they have one. Whether formally as a team member or informally as a legal liaison, your presence ensures legal risks are properly integrated into the organization’s overall risk analysis.

If no such function exists, consider forming a cross-functional risk working group. Include representatives from finance, operations, compliance, IT, HR, and the business units. The purpose is to regularly assess and prioritize enterprise-wide risks, ensuring accountability and follow-through. In today’s business climate, in-house counsel cannot operate in a silo. Collaboration with other departments turns risk analysis from a reactive to a proactive function.

Step two: What you need to know

Effective risk assessment starts with understanding three things:

- The company’s strategy: What are the short- and long-term business goals?

- The company’s risk appetite: How much risk is leadership willing to tolerate to achieve those goals?

- The right questions to ask: To guide your analysis effectively, consider this checklist of essential questions:

- What type of risk is this — legal, strategic, or mixed?

- What scenarios could trigger the risk?

- What is the likelihood of those scenarios occurring?

- Can third parties like vendors, regulators, and customers introduce or amplify the risk?

- What kind of harm could arise such as monetary loss, operational disruption, reputational damage, regulatory penalty, or personal injury?

- What are the best-case, worst-case, and most likely outcomes?

- What is the game theory here? If we do this:

- What happens in the short term?

- What happens in the long term?

- What options do we have to manage this risk?

- Can we train employees or revise policies?

- Do we need contract protections, such as indemnity clauses or limitations on liability?

- Is insurance available or sufficient?

- Should we delay or accelerate action?

- Should we accept the risk in exchange for value?

- Are there industry standards or benchmarks we can measure against?

- How can we monitor the risk over time, and what are the trigger points for escalation?

- How could this impact our reputation?

- Are the right people making the decision about this risk?

- Even if this is legal, should we do it?

Sometimes the last item on the checklist is the most important.

Step three: Be aware

While risk occasionally becomes apparent through formal channels — or with the help of artificial intelligence — lawyers can more effectively identify business and legal risks by actively participating in strategy, planning, and deal meetings.

Using the checklist above, create a habit of scanning for red flags as you listen and participate in discussions. At a minimum, ask yourself:

- Could this attract regulatory scrutiny?

- Could it upset customers, partners, employees, or investors?

- Would the outcome be defensible if it appeared in the media or before a court?

- Have competitors faced problems doing something similar?

- Could this involve safety, cybersecurity, or environmental impact?

Your ability to constructively ask these questions early in the discussion makes you a partner, not a problem.

Step four: Quantify the risk

In risk discussions, a common question is, “How good or bad could this be?” To address this effectively, it’s essential to speak the language of business — numbers.

Being able to discuss risk numerically is crucial for engaging and gaining insights from other parts of the business. You can start with what is known as the “risk equation:”

Risk value = Probability of the event × consequence, such as cost or value

It is pretty straightforward. Here are some examples:

- A class action settlement risk:

- 20% chance of liability × $5 million in damages = $1 million risk value

- An M&A deal with regulatory risk:

- 60% chance of approval × $30 million in incremental revenue = $18 million in potential upside

This analysis doesn’t have to be perfect. It just needs to be reasoned and consistent with how the business evaluates other decisions.

Step five: Report it

Lastly, once you’ve identified and evaluated a risk, you must communicate it clearly to the right people. This might be a formal written report, an email, or simply a discussion at a meeting.

Regardless of format, your communication should cover five elements:

- What the risk is.

- The likelihood of occurrence.

- The range of possible outcomes.

- Options to mitigate or instigate.

- Your recommendation and rationale.

Regardless of the reporting method you choose, it’s crucial to be aware of how attorney-client privilege works. This can be tricky for in-house lawyers, because the privilege only attaches when you are providing legal advice, not business advice. Know which applies to your discussion.

For example, if you are discussing litigation or a potential regulatory investigation or approval process, that is likely covered by attorney-client privilege. But, if you are providing an opinion about supply chain issues, that could be deemed as business advice. Regardless, always consider the potential for your written communications to be disclosed during litigation or investigations.

For these reasons, it’s important to craft your messages thoughtfully and strategically. Label documents appropriately, limit distribution, and separate business advice from legal advice when necessary.

Next steps

Learning about and managing risk is a key task for all in-house lawyers. In addition to the above, consider the following:

- Be proactive, not just reactive — get involved.

- Learn to think like a risk professional — spend time perfecting this part of your job.

- Think, talk, and write like a business professional— quantify risks and align your advice with commercial goals in mind.

- Educate others — train and encourage employees on how to flag, document, and escalate potential risks.

- Accept that you won’t catch everything — focus on material risks that impact the company’s business strategy and goal, not every theoretical hazard.

In-house lawyers are not just legal advisors anymore. They are strategic risk managers and enterprise enablers. With the right mindset, tools, and partnerships, in-house counsel can help the company take the right risks and avoid the wrong ones.

If you have access to Thomson Reuters risk solutions or Practical Law, you have dozens of tools to help you spot and manage risk.