How to organize and conduct a legal due diligence review for US public and private deals

← Legal terms • due diligence • legal due diligence

Jump to ↓

| Overview of legal due diligence |

| Public M&A deals |

| Private M&A deals |

| Use a checklist |

| M&A due diligence tools |

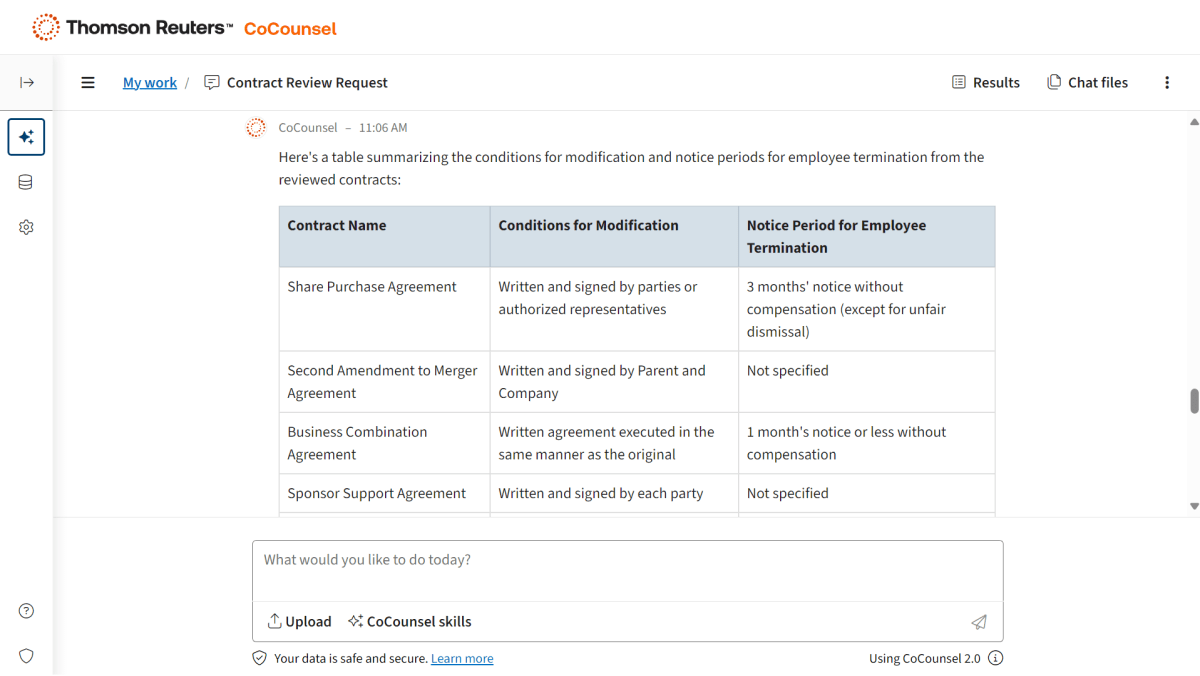

CoCounsel Legal

Bringing together AI, trusted content and expert insights in due diligence

Go professional-grade AI ↗Overview of legal due diligence

Due diligence is the heart of a successful merger or acquisition. Legal due diligence involves a comprehensive review of a target company’s business, legal, financial, operational, and other relevant details to evaluate its suitability for acquisition. The process is intended to identify any potential risks or liabilities that could impact the transaction. It can be costly, time-consuming, and frustrating but it’s absolutely essential. Diligence is how lawyers help ensure that a deal that looks good on paper delivers on its promised value and benefits.

Legal due diligence can be complex within an already complicated transaction management workflow, so it’s easy for a buyer to get lost in the details. And the time pressures on a deal are such that a buyer may feel the urge to rush through diligence, and so miss key information. That’s why it’s so important that prospective buyers have a blueprint to follow.

Steps to conduct legal due diligence for public mergers and acquisitions

1. Organizing the due diligence process

Before you craft your diligence review, start with the basics: analyze the deal itself. What type of merger is it — a reverse merger? Is it a hostile takeover or more a merger of equals? Among the other information you will need to know:

- The parties involved in diligence — will third-party consultants be part of the process?

- The deadlines — is there a date by which diligence needs to be completed? Is this predicated on another process being underway or completed (such as regulatory approval)?

- The end product — does the client want an oral or written report? Detailed analyses or a concise summary of where things stand?

2. Assemble the due diligence team

Once the team is organized, determine how workflow will be handled. This is crucial to keep the M&A process streamlined. How will you track which documents get reviewed, and when, and who is responsible for handling particular materials? You should also determine how results will be communicated to attorneys conducting merger negotiations (see below).

Other questions to answer at this stage include whether local counsel is needed. For example, if the target company is located in a state or country that your firm has no connections with; whether any specialist counsel will be needed, such as someone with real estate or tax expertise; and who the diligence contact person at the other company’s law firm is.

3. Submit the due diligence request

As there is much to process during diligence, your team should focus on finding relevant information pertaining to deal negotiations. For example, the target’s management/ownership structure. Your diligence team should know:

- What actions require the consent of the board of directors? Can the board change policies without holding a shareholder vote?

- Who can sign documents on behalf of the target and its subsidiaries?

- Are there restrictions on the ability of the target to borrow, to refinance debt, to guarantee debt?

Also essential — finding out the biggest potential impediments to the deal closing.

- Are there anti-takeover defenses? For example, is there a poison pill, a staggered board of directors, blank-check preferred stock, or onerous advance notice provisions?

- Are there restrictions on the target that could impact proposed deal financing? Are there payments or benefits owed to a third party that could affect the deal’s economics?

- Where do the biggest potential liabilities lie? Could anything restrict the target from operating normally after the closing?

You’ll be looking for, among other things:

- Target governing documents — certificate of incorporation by-laws — and records of business such as minutes of boards of directors meetings and internal communications.

- Target’s current market status — how much stock is outstanding? How much is authorized? Are there multiple classes of stock? Can there be further issuances?

- Subsidiary information of how many and what types — wholly-owned, partially-owned, etc. — of subsidiaries does the target have?

- The target company’s contracts such as customer and supply contracts, operating contracts, and licenses.

4. Distribute and organize materials

The information that you discover in diligence needs to be organized and distributed properly. Some questions to answer by this stage include:

- How best to organize materials? Are you storing material in databases or in a virtual data room? If so, will there be tiered levels of access, given the sensitivity of materials?

- Are you using AI for M&A due diligence? Does it make the most sense to classify materials alphabetically, numerically, chronologically, etc.? The more precise your organizational system, the easier it will be to find information when needed in negotiations.

- Will you need to create a due diligence index, or print an index, from the data site? A paralegal can often help with this process using legal business management platform that integrates with AI tools.

- What is your firm’s record retention policy? Review confidentiality agreements to ensure you’re in compliance with dissemination, retention, and use restrictions.

5. Review key sources of information

SEC filings

In a public deal, the target’s SEC filings are critical to diligence review. A team should assess all publicly available materials via the SEC’s EDGAR system and request any other SEC documents in the target’s data room. You’ll need to determine whether the target has restated or made significant corrections to recent filings, and if these changes present any risk to the merger, or to the buyer’s plans for the target post-merger.

Sarbanes-Oxley Compliance

Public companies are subject to disclosure and corporate governance requirements of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX). You will need to perform diligence on the target’s protocols and procedures in connection with SOX. This is serious business, as the penalties for non-compliance can be severe. A buyer will have to decide how to address any penalties and legal repercussions from the target’s non-compliance.

6. Determine if a third party will rely on the due diligence report

A buyer may wish to share the due diligence report with a third party (for example, a bank financing the deal). Doing so often requires the third party to execute a non-reliance letter stating that sharing the report does not serve as a waiver of attorney-client privilege. However, such a statement is often not enough for a court of law.

So if the client plans to share the diligence report, remind your client that preservation of attorney-client privilege is not assured in this situation, that a third party may review the report with a different objective than the client’s, and that the report may disclose business sensitivities that the client may wish to keep confidential.

7. Analyze anti-assignment clauses

There are three general types of transactions that could trigger anti-assignment clauses:

- Asset purchase transactions — if assets (including contracts) of the target company are to be transferred to the buyer, this typically triggers an anti-assignment clause unless an express exception to the clause is included in the contemplated transaction.

- Stock purchase transactions — should the buyer acquire ownership of the target’s equity, rather than assets, the target company will continue to own its assets (including contracts) after the closing. That’s why a stock acquisition generally does not trigger an anti-assignment clause.

- Merger transactions — whether an anti-assignment clause prohibits a merger depends on the type of merger, any applicable state law, and the language of the anti-assignment clause in question. If the clause is a simple anti-assignment clause prohibiting “assignments,” a forward or forward triangular merger is unlikely to trigger the anti-assignment provision. However, such a merger could trigger a more broadly-worded anti-assignment clause.

8. Analyze change of control clauses

A change of control clause in an agreement gives a party certain rights such as consent, payment, or termination in connection with a merger or acquisition.

When conducting a due diligence review, counsel should locate and analyze any change of control prohibitions to determine whether the contemplated transaction will trigger a change of control clause under the law of the applicable jurisdiction, and the related consequences.

Practical Law Clause Finder

Access the best terms for your agreement and streamline your drafting.

Explore Clause Finder ↗Steps to conduct legal due diligence for private mergers and acquisitions

1. Define the due diligence task

As with public company due diligence, know what your client fundamentally needs. Before due diligence review, establish:

- The amount of the due diligence budget

- Aspects of diligence review: its scope, its deadlines, what type of report is expected

- Whether outside consultants will be needed

- The process of communicating to deal parties. For example, you may be required to communicate through a third party, such as the client’s investment banker.

2. Assemble the due diligence team

The due diligence team’s make-up depends on transaction specifics, but usually includes legal, business, accounting and tax specialists.

Depending on the complexity of the transaction, its management, and the budget allocated, teams can range wildly in size. But it’s always important to have a point person to coordinate the process —this task often falls to a junior lawyer.

3. Submit the due diligence request

While sometimes a private seller will make diligence materials available, often a buyer needs to submit a request for information. These are typically requests for general or specific documents, organized by topic, and supplemented with further requests once negotiations get underway.

Counsel should tailor questions to the specific target business and the industry in which it operates.

4. Get access to sources of information

In a private deal, the diligence team often lacks such resources as the EDGAR system to monitor the target company’s financial statements. They instead will need access to the target company’s privately-held financials, which may only be available on the target’s premises or in a virtual data room.

A private company may not want to share what it considers trade secrets, particularly if the buyer is a competitor. After all, if the deal doesn’t succeed, the potential buyer will have gained insight into a rival’s operations. So a private seller may seek to impose substantial restrictions on the dissemination of materials before the deal is consummated. They may demand the right to redact sensitive information in documents, for instance.

5. Watch out for certain materials and common issues

For a private company, ownership documents are paramount interest. You will be looking for such material as:

- Capitalization and equity ownership — who owns equity in the target? Is there equity outstanding? Is there pending or ongoing litigation related to equity ownership?

- Will equity-holder votes or consents be required to approve the deal?

- Are there restrictions on the transfer of equity? Do equity holders have preemptive rights in future issuances?

6. Delegate specialist reviews

As with public deals, some due diligence review may require legal specialists and outside consultants such as accountants and insurance consultants. For example, a supply contract may contain significant provisions relating to the target’s intellectual property holdings, and thus need review by an IP attorney.

7. Record and communicate findings

Due diligence summaries

Due diligence summaries are an ongoing record, often compiled on a daily or weekly basis, of what the due diligence team has reviewed to date. It’s essential for the creation of a comprehensive due diligence report.

Due diligence report

The ultimate product of a due diligence review, the due diligence report can range from short oral presentations to lengthy, annotated documents, depending on the client’s needs. The report should be clear and actionable. If the report is lengthy, counsel typically provide an executive summary highlighting significant findings.

8. Analyze anti-assignment and change of control clauses

As with public deals, anti-assignment clauses could be triggered by a merger, depending on the merger’s nature. With private deals, a stock purchase transaction being a trigger is potentially an even greater factor, as a private acquisition can be achieved by the buyer taking ownership of the target’s privately-held equity, which may lie in relatively few hands.

Change of control clauses, as in public transactions, will need to be analyzed to ensure that they are not triggered upon a sale of assets or a change of ownership.

Practical Law

Get expert how-to guidance, clear explanations of current law, and time-saving tools and templates to give you a better starting point

View all plans ↗Use a checklist

There are of course many more nuanced and additional steps. It’s not hard for a diligence team to miss an important step. That’s why keeping a diligence checklist helps counsel stay on course.

A checklist is your diligence team’s roadmap. It makes sense to organize it chronologically, in terms of which tasks need to be done and when. For example, a high-level diligence checklist could be organized like so:

- Assembling the team

- Submitting the due diligence request(s)

- Assessing and organizing materials

- Reviewing information and determining if specialist review is needed

- Communicating team findings from diligence

For more, see this sample M&A due diligence checklist

Legal due diligence tools for legal teams

Technology is now vital to conduct due diligence — the days of lawyers digging through boxes of paper documents are part of the past. How can a technology solutions manager locate the best tools for their diligence teams? There’s a lot to assess before making that choice.

The potential for technology in due diligence is as vast as it’s transformative. Properly-trained artificial intelligence systems can fully automate document identification, using such parameters as date, language or type, and then extract all relevant clauses. This enables lawyers to dig extensively into a document load at a much faster pace, regardless of how substantial a collection it is.

Once it has completed its analysis and retrieval functions, diligence software can swiftly organize all documents for review, aiding with the diligence team’s analysis. By making the “nuts and bolts” tasks machine-assignable, this frees team attorneys to address any diligence issues that require greater legal expertise.

The key phrase, however, is properly-trained AI. Relying on “open” AI technology to do complex legal document searches and discovery can go wrong very fast, and could be potentially disastrous in a diligence situation. Clients need information quickly, but it also has to be as accurate as possible, and to be relevant to the deal negotiation.

More resources

- Case study — How Slaughter and May uses HighQ

- White paper — Today’s M&A industry: Prepare to win more business

AI news and insights

Industry-leading insights, updates, and all things AI in the legal profession

Join community ↗